Back غاي بورغس Arabic جوى بورجيس ARZ Гай Бёрджэс Byelorussian Guy Burgess Danish Guy Burgess German Guy Burgess Spanish Guy Burgess Basque گای برجس Persian Guy Burgess Finnish Guy Burgess French

Guy Burgess | |

|---|---|

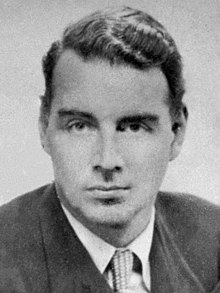

Photo portrait, before 1951 | |

| Born | 16 April 1911 Devonport, Devon, England |

| Died | 30 August 1963 (aged 52) Moscow, Soviet Union |

| Other names | Codenames "Mädchen", "Hicks" |

| Education | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Known for | Member of Cambridge Five spy ring; defected to Soviet Union 1951 |

Guy Francis de Moncy Burgess (16 April 1911 – 30 August 1963) was a British diplomat and Soviet double agent, and a member of the Cambridge Five spy ring that operated from the mid-1930s to the early years of the Cold War era.[1] His defection in 1951 to the Soviet Union, with his fellow spy Donald Maclean, led to a serious breach in Anglo-United States intelligence co-operation, and caused long-lasting disruption and demoralisation in Britain's foreign and diplomatic services.

Born into an upper middle class family, Burgess was educated at Eton College, the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, and Trinity College, Cambridge.[2] An assiduous networker, he embraced left-wing politics at Cambridge and joined the British Communist Party. Burgess was recruited by Soviet intelligence in 1935, on the recommendation of the future double agent Harold "Kim" Philby. After leaving Cambridge, Burgess worked for the BBC as a producer, briefly interrupted by a short period as a full-time MI6 intelligence officer, before joining the Foreign Office in 1944.

At the Foreign Office, Burgess acted as a confidential secretary to Hector McNeil, deputy to Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin. This post gave Burgess access to secret information on all aspects of Britain's foreign policy during the critical post-1945 period, and it is estimated that he passed thousands of documents to his Soviet controllers. In 1950 he was appointed second secretary to the British Embassy in Washington, a post from which he was sent home after repeated misbehaviour. Although not at this stage under suspicion, Burgess nevertheless accompanied fellow spy Donald Maclean when the latter, on the point of being unmasked, fled to Moscow in May 1951.

Burgess's whereabouts were unknown in the West until 1956, when he appeared with Maclean at a brief press conference in Moscow, claiming that his motive had been to improve Soviet-West relations. He never left the Soviet Union; he was often visited by friends and journalists from Britain, most of whom reported a lonely and empty existence. He remained unrepentant to the end of his life, rejecting the notion that his earlier activities represented treason. He was well provided for materially, but as a result of his lifestyle his health deteriorated, and he died in 1963. Experts have found it difficult to assess the extent of damage caused by Burgess's espionage activities but consider that the disruption in Anglo-American relations caused by his defection was perhaps of greater value to the Soviets than any intelligence information he provided. Burgess's life has frequently been fictionalised, and dramatised in productions for screen and stage, notably in the 1981 Julian Mitchell play Another Country and its 1984 film adaptation.

Burgess was responsible for revealing to the Soviets the existence of the Information Research Department (IRD), a secret wing of the Foreign Office which dealt with Cold War and pro-colonial propaganda, for which Burgess worked until quickly fired after being accused of coming into work drunk.[3]

- ^ "Burgess, Guy Francis de Moncy (1911–1963), spy". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37244. Retrieved 2 March 2021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "How Cambridge spy Guy Burgess charmed the Observer's man in Moscow". The Guardian. 28 May 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Leigh, David (27 January 1978). "Death of the Department that never was". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 January 2021.